|

For many divers in the Caribbean spending time with a shark underwater, however briefly, is the pinnacle of a diving day or even a diving trip, but this is becoming all too rare. These beautiful animals are being driven to extinction by modern fishing practices. Over the years I'd snapped a few grainy pictures of hammerheads off in the distance and I was happy to get them, but the first time I was lucky enough to get in close for a proper shot of a Scalloped Hammerhead, it had a large steel hook with a wire leader trailing from it's mouth!

overfishing of Caribbean Sharks:

A recent report by the Pew Charitable Trusts says that global shark populations have declined by as much as 70 to 80 percent, a brink they may well not be able to recover from. Like most apex predators, sharks reach sexual maturity very late in life (10-20 years) and may only produce one or two pups a year, so there is no hope of these stocks being replenished if things continue as they are. A conservative estimate is that 100 million sharks are being killed every year.

The Caribbean shark fishing industry boomed in the 1950's with demand for their liver, skins and fins, and tripled during the 80's. Caribbean shark and ray landings peaked in 1990, with more than 9 million metric tons that year. It was obviously unsustainable but has had far-reaching impacts on the Caribbean as a whole. Sharks have been in the world's oceans for over 400 million years and they play a crucial role in the health of Caribbean reef ecosystems. They are known as "keystone species" and their role is to keep other fish populations in check, so that the delicate balance of a coral reef is maintained. Dr. Stuart Sandin of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography has been studying why so many degraded reefs in the Caribbean are being taken over by algae. It is called an ecological cascade effect, where the removal of one key species changes the entire system. Once the sharks are removed from a reef other carnivore species such as groupers move in to fill the void. These groupers then overfeed on the herbivores such as the surgeonfishes and parrotfishes that are normally responsible for clearing the coral of algae. And no, the fact that we are also putting species like the Nassau Grouper on the Critically Endangered Species List is not helping the situation. It's all inter-connected down there. By removing the keystone species we are placing the whole reef, and even the livlihoods of people who depend on them, at risk.

Click on the image above to download a very good article by Oceana.org on the importance of sharks for healthy reefs, or click below to see a quick video from the PEW Charitable Trusts.

These cascading effects are difficult to predict and even more difficult to convince people of, the connections between sharks and other animals just seems too tenuous. But one well-documented example is the fall of a US east coast scallop fishery. With the overfishing of sharks (mostly Blacktips) off the coast of North Carolina, the local population of Cow-Nose Rays quickly grew. These rays were able to move into new territories and they decimated the scallop populations to a point from which they may never recover. Shark fishing in that one area led to the ruin of an entire community of scallop fishermen.

Pelagic Sharks and Longline fishing:

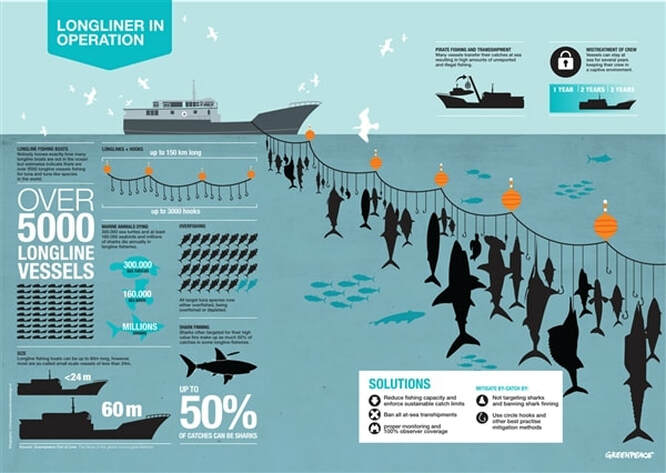

The fastest decline is actually happening far from our reefs. One third of pelagic shark species like the Oceanic Whitetip, Mako and Hammerhead Sharks are all facing extinction. (Click here to read the IUCN report). They are mostly caught on longlines. Longline fishing is where vessels put out many miles of line, with thousands of baited hooks. They are targeting commercial species such as tuna and swordfish but sharks get caught as well, often 25 or even 50 percent of the catch.

Click above for the full infographic by Greenpeace, or click here for more on longline fishing.

There is another cascading effect from the removal of large sharks from the world's oceans, this time involving seabirds. One of the biggest predators of seabirds are Tiger Sharks and since their numbers are now so low, researchers have seen the population of some seabirds increasing dramatically. This means more pressure on their food source: juvenile fish species such as tuna and jacks. Ironically the lower catches in the modern tuna and jack fishing industries are being compounded by the overfishing of our shark species.

Shark finning:

This is where things get really ugly. Sharks are also directly targeted for their fins. Sharks are caught, their fins sliced off and the bodies are dumped back into the water still alive. The Asian market's demand for shark fin soup drives this industry, where a single bowl of soup can cost up to $100.

Shark fin soup was once reserved for only the ruling classes, but with the rapid expansion of the Chinese economy, it is now seen as a sign of prestige and wealth. Consumption doubled in the last two generations. Recent public pressure has led to finning being banned by 70 regional bodies and countries. Even the Chinese government says it will no longer serve shark fin soup at official banquets and government functions. But while there is still a demand, sharks will continue to be targeted. According to some estimates, up to 73 million sharks are caught in the finning trade each year.

Click above to see Gordon Ramsey's investigation into the shark fin trade, from restaurants to fishing boats. (Warning: contains disturbing footage and of course Ramsay's colorful language).

The Future of sharks:

Divers and dive tourism can help the situation by using the power of our wallets. It's an uphill battle to convince people in government that sharks are not the mindless killing machines as portrayed on television and in movies. But show them how a country can make more money by protecting their shark populations, and their ears prick up and they may actually do something about it.

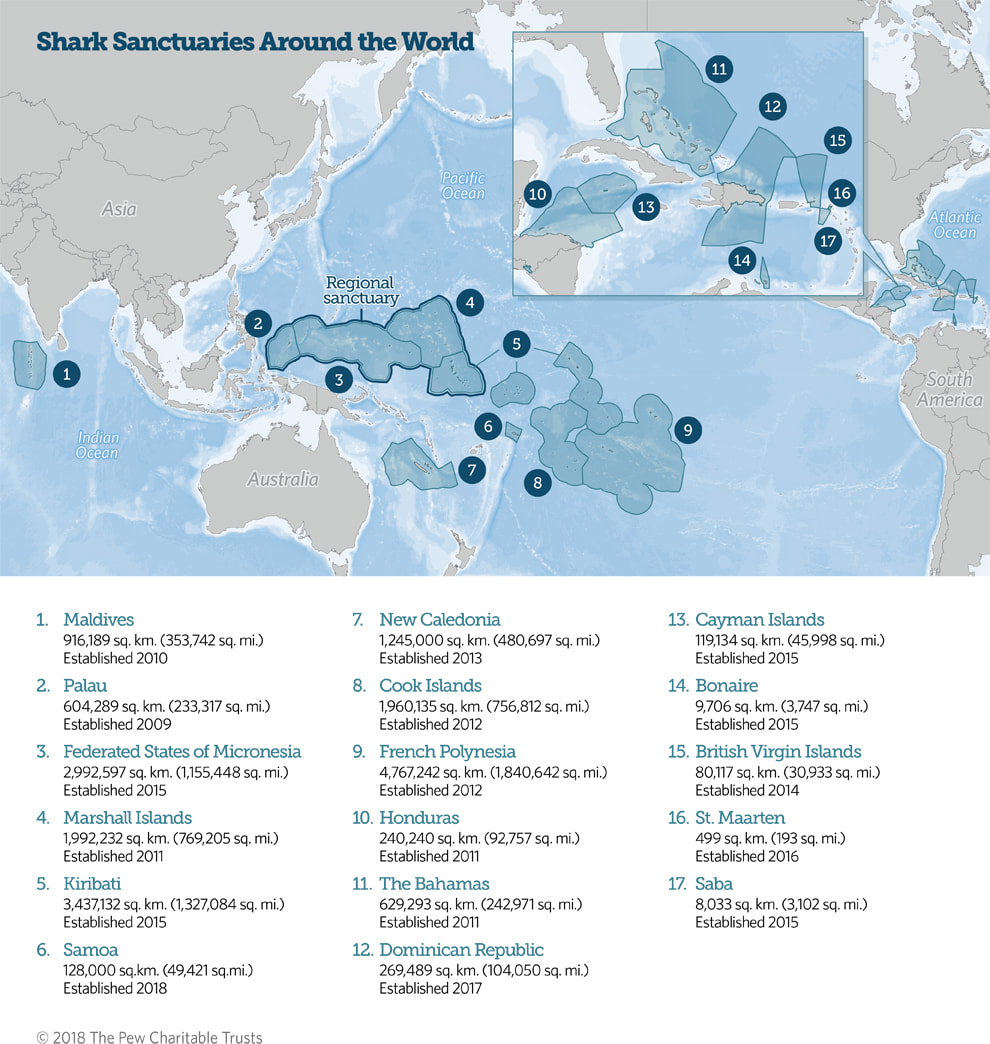

As Jill Hepp (director of global shark conservation at the PEW Charitable Trust) puts it: “Many countries have a significant financial incentive to conserve sharks and the places where they live.” Her report found that tourism draws almost 600,000 people annually to watch sharks from hammerheads to great whites, supporting 10,000 jobs in 29 countries. The Bahamas is a good example: the shark diving industry there contributes approximately $113.8 million a year to the economy in direct and value-added expenditures. Compare that to the $50-$60 that a dead shark brings in. I've never been a fan of baited shark dives, for a variety of reasons. I'd rather see them by chance and behaving naturally, but there can be no doubt that it creates more awareness of both how beautiful and important these majestic animals are and sharks need all the public support they can get. It has helped to create a number of shark sanctuaries around the world. Palau led the way with the first shark sanctuary in 2009 quickly followed by the Maldives, two countries that are very dependent on their dive tourism. Here in the Caribbean, it was Honduras that first woke up and declared all of it's waters off limits to commercial shark fishing in 2011, and the Bahamas soon followed suit. Other Caribbean nations have since created their own sanctuaries and hopefully the trend will continue. Sharks can be highly migratory and don't observe national boundaries, so neighboring countries need to get on board and add their support, if not for the sake of the sharks then for their own reefs and economies.

Of course having laws in place and actually being able to enforce them are different matters. Shark fishing still continues even within these sanctuaries (click here to see more) but it is a good start. If far-away governments can be convinced that sharks are important to the economy, small-scale fisherman need to be convinced that targeting sharks is actually bringing down the whole ecosystem they depend on. Fighting that very human short-term thinking is still one of the greatest challenges for shark advocates worldwide.

Yes, Caribbean reefs are changing. Overfishing, invasive species, warming sea temperatures, pollution and agricultural runoff are all taking their toll. But sharks are one of the key elements that we can actually do something about.

And who knows, maybe our kids might still have a chance to see a shark on a dive one day as well. Enjoy while you can and help support shark sanctuaries. Mickey Charteris

1 Comment

|

AuthorMickey Charteris is an author/photographer living on Roatan. His book Caribbean Reef Life first came out in 2012 and is currrently into it's sixth printing as an expanded fourth edition. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed