|

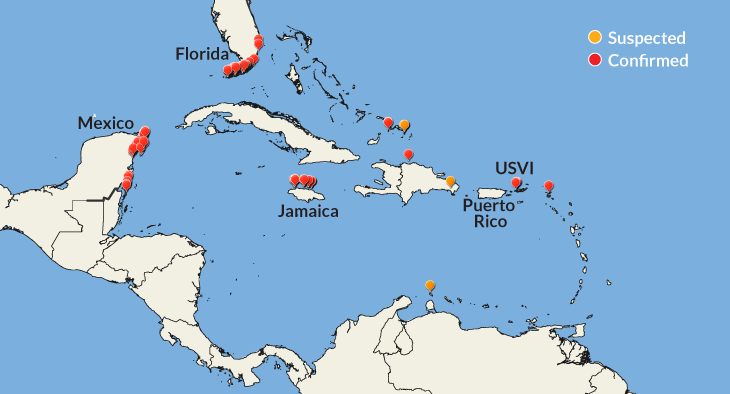

Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease, or "SCTLD", was first spotted in Florida in 2014 and it is now spreading incredibly quickly towards the greater Caribbean.

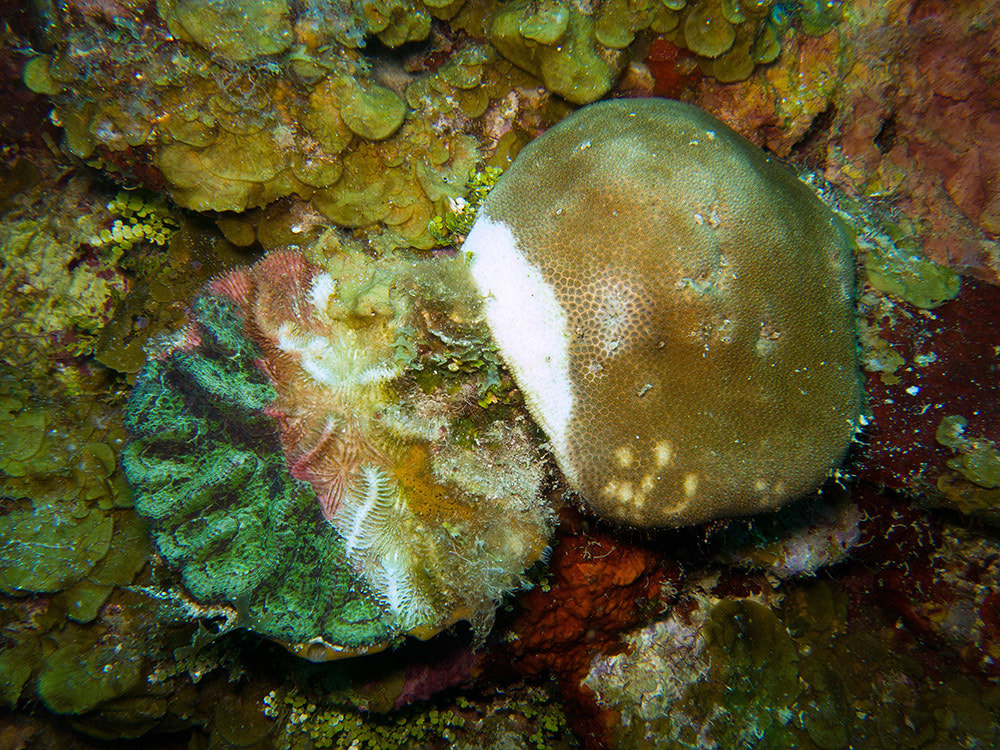

Divers in Florida, and now Mexico and beyond, are all too familiar with this new epidemic. The rest of us in the Caribbean need to be on the lookout: it's not a matter of if, but when it will hit our local reefs. "It's the most devastating coral reef disease we've ever seen," says Dr. Andy Bruckner, a research coordinator for the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Florida has recently lost over 75% of it's corals and some reports put the number at closer to 90-100%. Sint Maarten has lost over 60% of it's corals. Already this year reefs along the Yucatan have seen a 30% coral mortality rate with this disease and now this summer Belize has also begun reporting widespread infections. There is no longer any doubt, it's moving south. This devastating new coral disease is rampant, poorly-understood and incredibly virulent. The future of our Caribbean reefs hangs in the balance, and it seems that precious little can be done about it. Meet "Big Momma":

Big Momma was a familiar sight to divers in the Fort Lauderdale area. According to NOAA and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary: "This "Big Momma" was the largest known colony of Mountainous Star coral (Orbicella faveolata) in Southeast Florida. At more than 330 years old, it was older than the United States. It survived the industrial revolution, numerous hurricanes, and the many stressors associated with the rapid urbanization. "Big Momma" died in a matter of three to four months after contracting this tissue-loss disease."

This is what divers in the rest of the Caribbean have to look forward to this year... The Rapid Spread of Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease:

Click above to watch a video showing the recent Stony Coral Tissue Loss outbreak in Cozumel,

taken by Dr. Lorenzo Alvarez Filip, UNAM What is Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease?

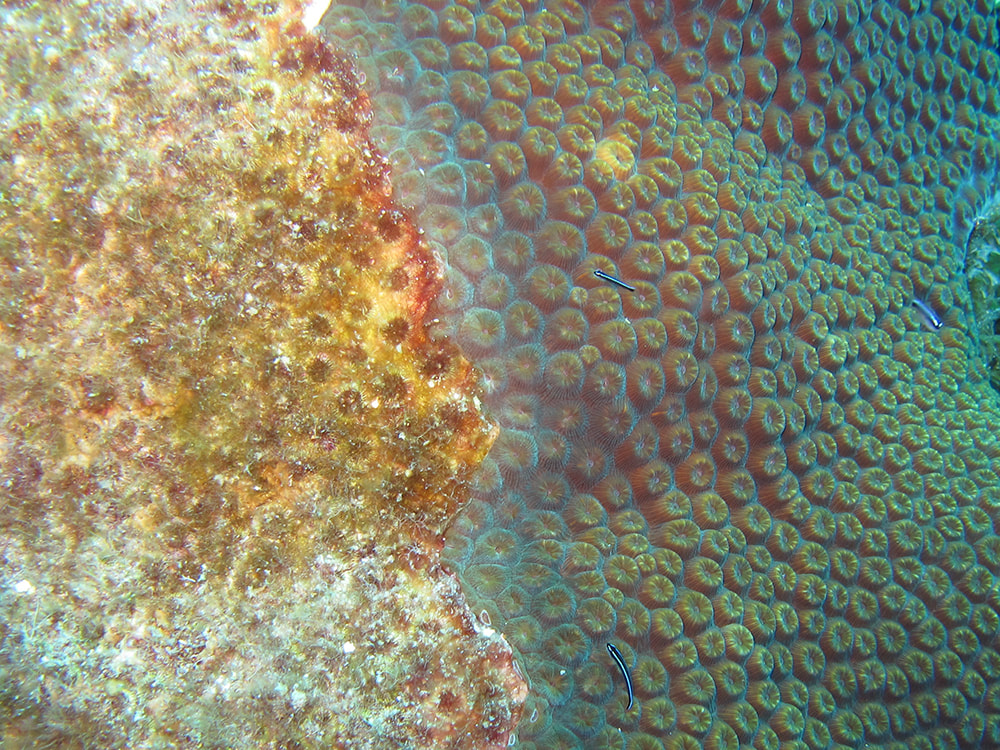

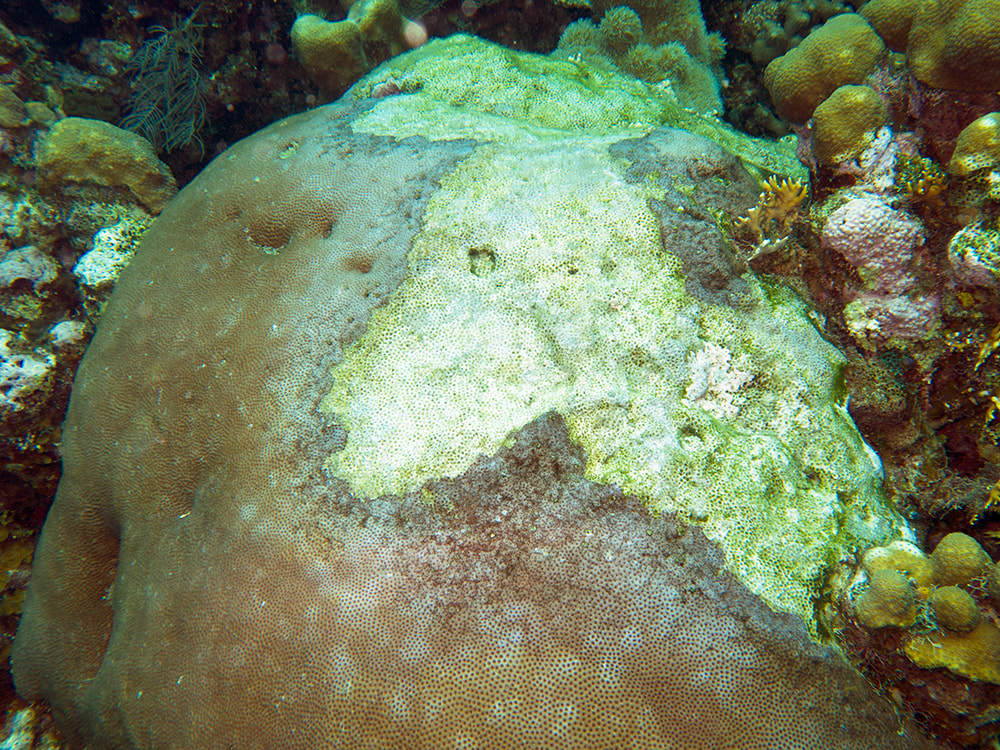

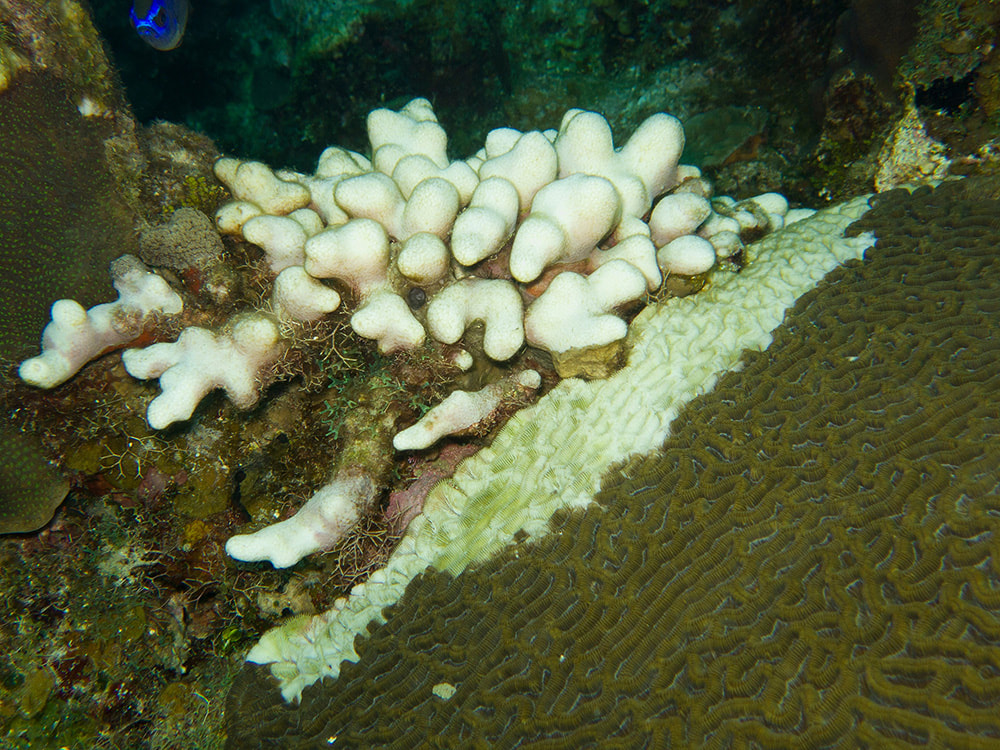

The short answer here is that no-one knows. It first shows up as white bands or lesions on live corals and the infected coral tissue sloughs off, leaving only the white skeleton exposed. It spreads quickly, sometimes killing off the entire coral colony in as little as a week. Like most coral diseases in the Caribbean it is thought to be bacterial, but it's causes and origin have yet to be identified.

It was first observed in Miami Dade County, just after the dredging of the federal channel at Port of Miami, when massive amounts of sediment were introduced onto local reefs. This could be just one factor, as reefs were already stressed from bleaching events and high levels of nitrogen in the surrounding water from agricultural runoff. (Click here for more on SCTLD in Florida). According to Dr. Brian Lapointe, a research professor at Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute: "Coral reefs have evolved over millions of years in clear, clean, low-nutrient water. They've coped with carbon dioxide and high temperatures before. What they have not had to cope with is carbon dioxide, high temperatures, and reactive nitrogen." The natural nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio on coral reefs is 16:1, but man-made nitrogen has been skewed in the areas where the disease began to an incredible ratio of 260:1. Clearly, human activity is to blame. Coral bleaching events in 2014 only made the corals more sucesptible to this new infection, and now it's on it's way south to attack otherwise healthy reefs.

"Changing Seas", a public television series produced by South Florida PBS, has recently made a very good documentary on Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease called "Corals in Crisis":

What makes "SCTLD" so virulent?

This new strain is the most virulent that marine microbiologists have ever seen, for a number of factors, making it far and away the biggest threat that the Caribbean region has ever faced:

* Many coral species affected -Unlike other coral diseases, SCTLD has affected over 20 species of the 45 Caribbean reef-building corals. * High prevalence - SCTLD disease is seen in many to all colonies of highly susceptible species. In Florida, 66-100 out of every 100 colonies surveyed were infected. * Rapid mortality - Once a coral is infected, it begins to rapidly lose living tissue and the colony dies within a period of weeks to a few months. * High rates of transmission -When SCTLD is present on a reef, it spreads very rapidly. Recent studies have suggested the disease is caused by a bacterial pathogen which can be transmitted via direct contact or directly through the water column. * Large geographic range - SCTLD outbreaks occur over large spatial scales. Over half of the Florida Reef Tract has been affected: > 96,000 acres since 2014. SCTLD is now found along the entire Mexican Caribbean coast and has affected 30% of all corals on this otherwise healthy habitat. * Long duration of the outbreak - Unlike other diseases, SCTLD has continued to spread continuously for more than four years in a row in Florida.

For a more in-depth look, the Reef Resilience Network has posted this 1 hour webinar on SCTLD:

Other Coral diseases:

Coral disease outbreaks around the Caribbean are nothing new. Before looking to see if Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease is appearing on your local reefs, here's a quick crash course in the diseases that, until now, have been the major threat to our reef ecosystems. Most of these can be seen as an expanding, colored band of infection that moves across a coral head, devouring the living tissue. Rates vary depending on the disease.

White Plague:

This is the coral disease that most closely resembles Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease. It affects most of the same coral species and has a similar rate of spread across each colony. The cause of this disease is one of the few that is actually known: a naturally occurring bacteria called Vibrio, that can take hold when corals are under stress from poor/warm water conditions or in areas with increased nutrient levels.

Here on Roatan I first began to document the spread of this disease just after a new mooring ball was put in place for a dive site, unfortunately called "Mickey's Place". This Agaricia plate coral, just below the new mooring, died off in less than two months. Honored to have a dive-site named after me, I was gutted to see that increased human activity around this pristine section of wall coincided with such degredation.

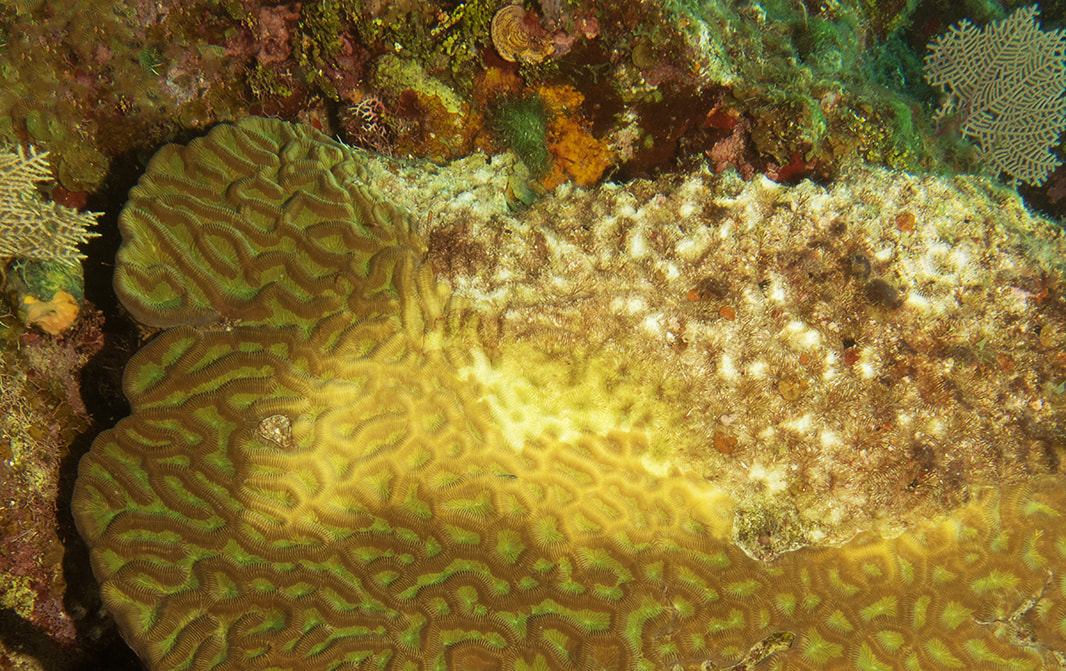

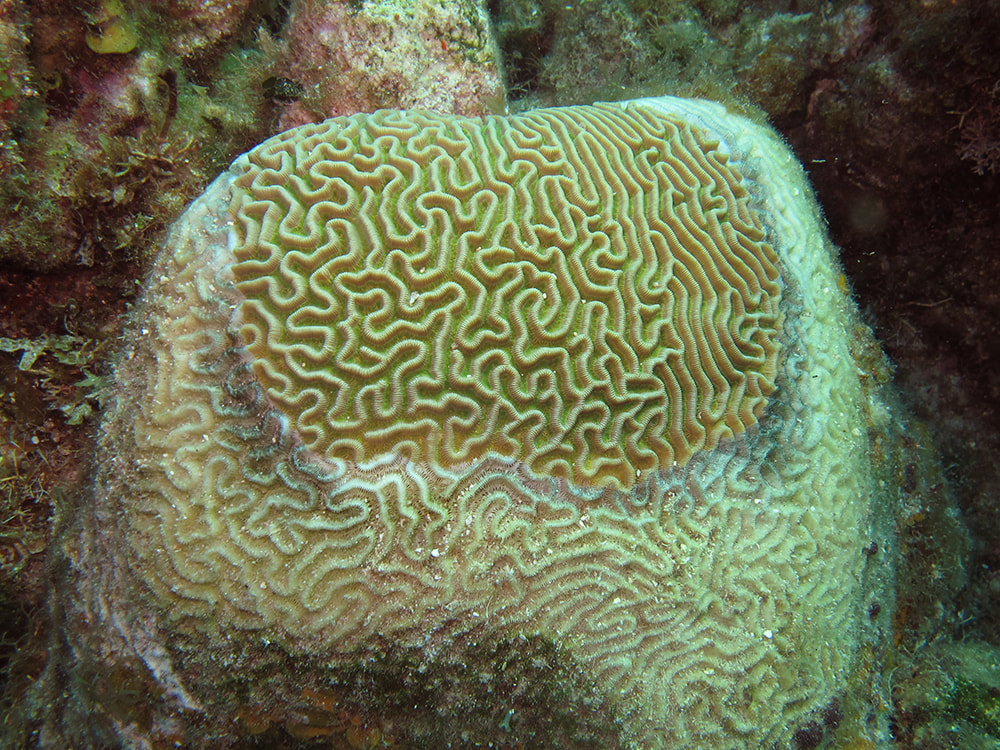

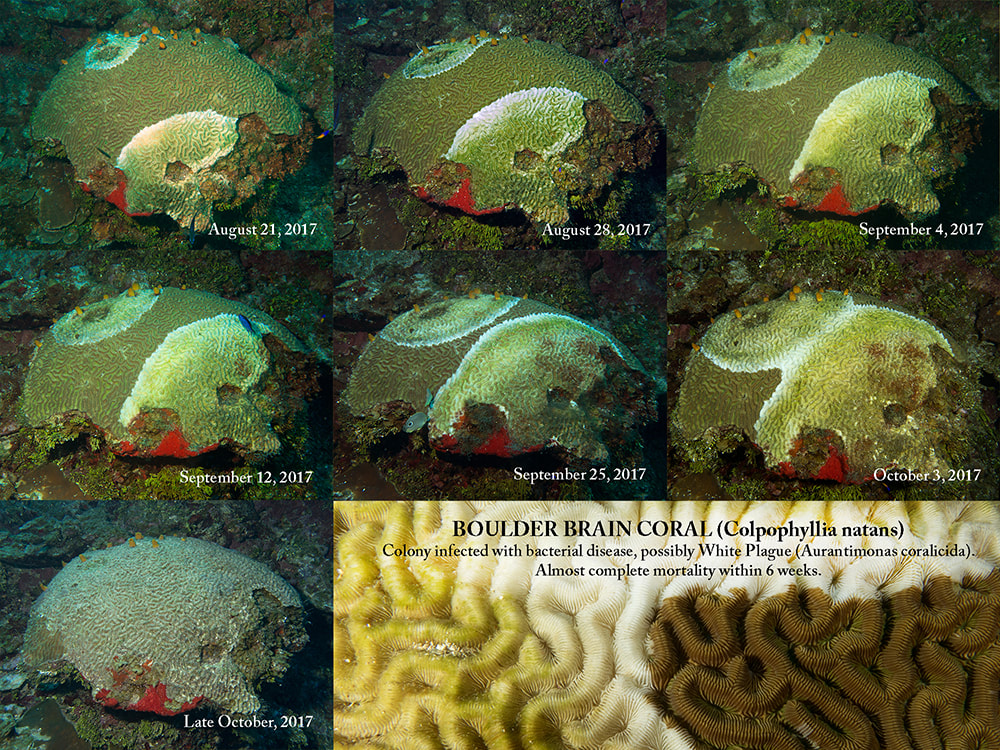

Closer to home, I was able to record the spread of White Plague across a Brain Coral (Colpophyllia natans) on "Overheat Reef", the regular shore dive that I do in front of my house. I visited this coral head every week for nearly two months, and felt helpless as I slowly watched this colony succumb to the disease.

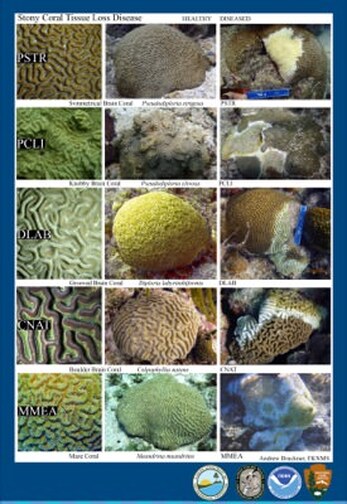

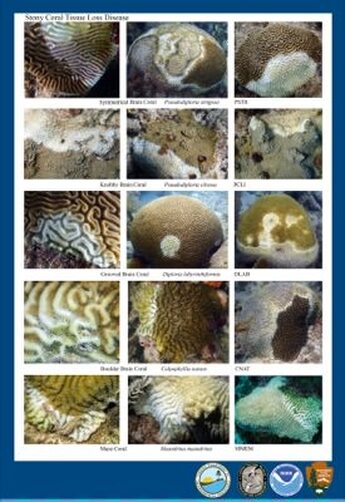

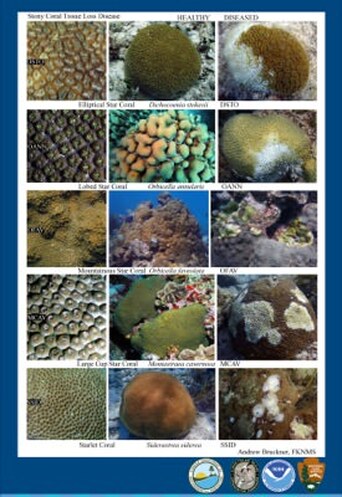

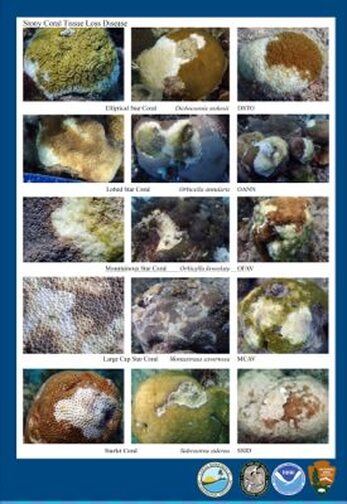

NOAA and the National Marine Sancuaries have made these downloadable cards available to help divers decide if what they are looking at is in fact Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease or another type of disease, or some other naturally ocurring damage to our corals. To get the full resolution cards, click on the thumbnails below:

Another very useful resource are these downloadable and printable underwater cards for identifying the most common Caribbean Coral Diseases, made available by The CRTR (Coral Reef Targeted Research) Disease Working Group:

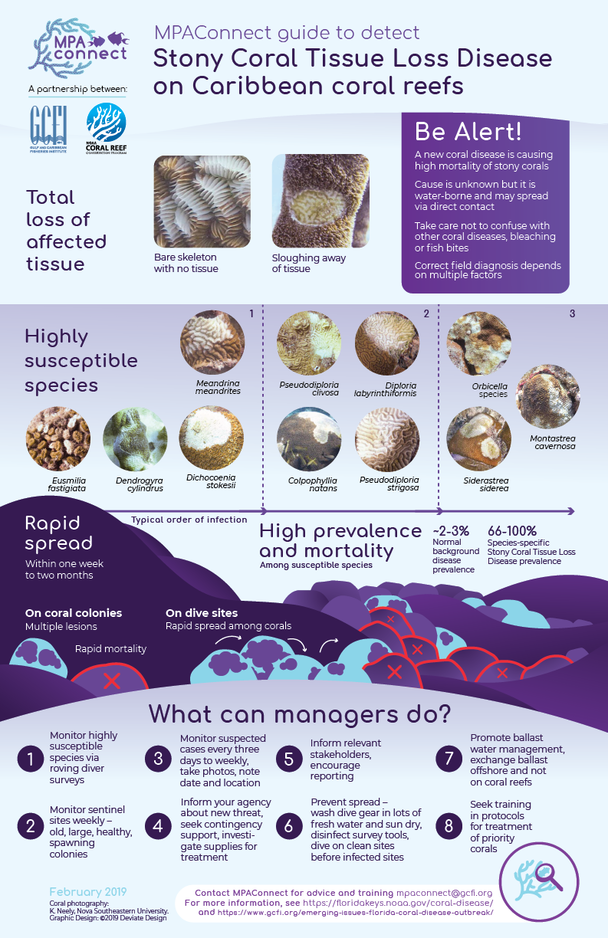

How to identify Stony Coral Tissue loss Disease:

Rather than a single, colored line of expanding tissue loss, colonies infected with Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease may develop multiple lesions across the whole surface that quickly spread outwards, often connecting and continuing to envelop the entire coral colony. The mortality rate for this new disease is estimated at between 66-100%.

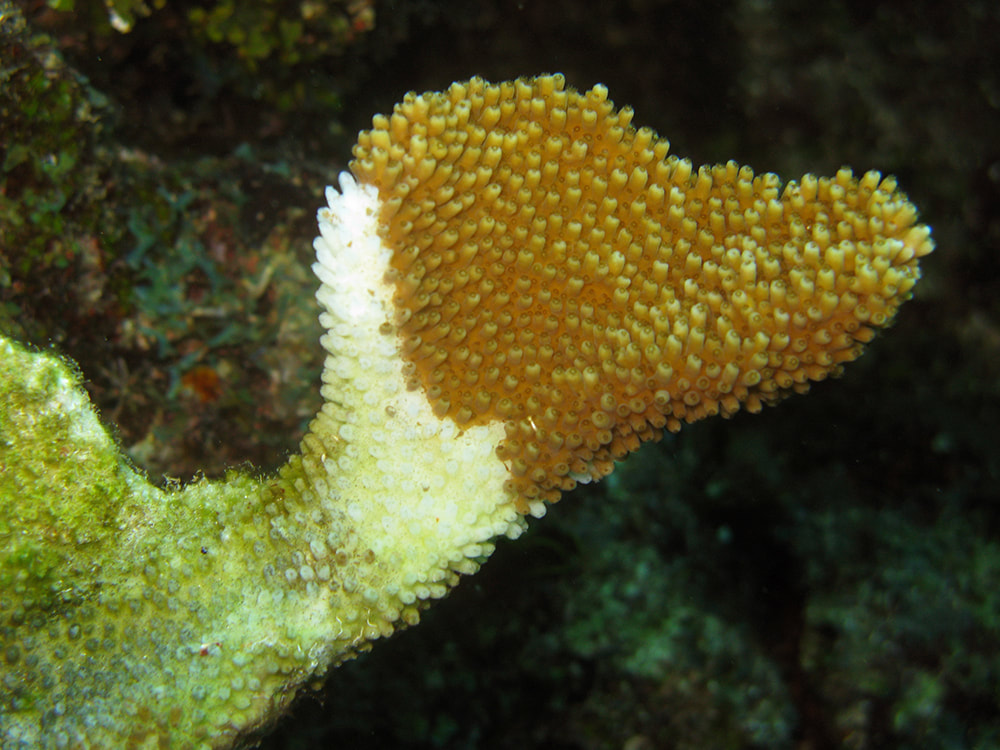

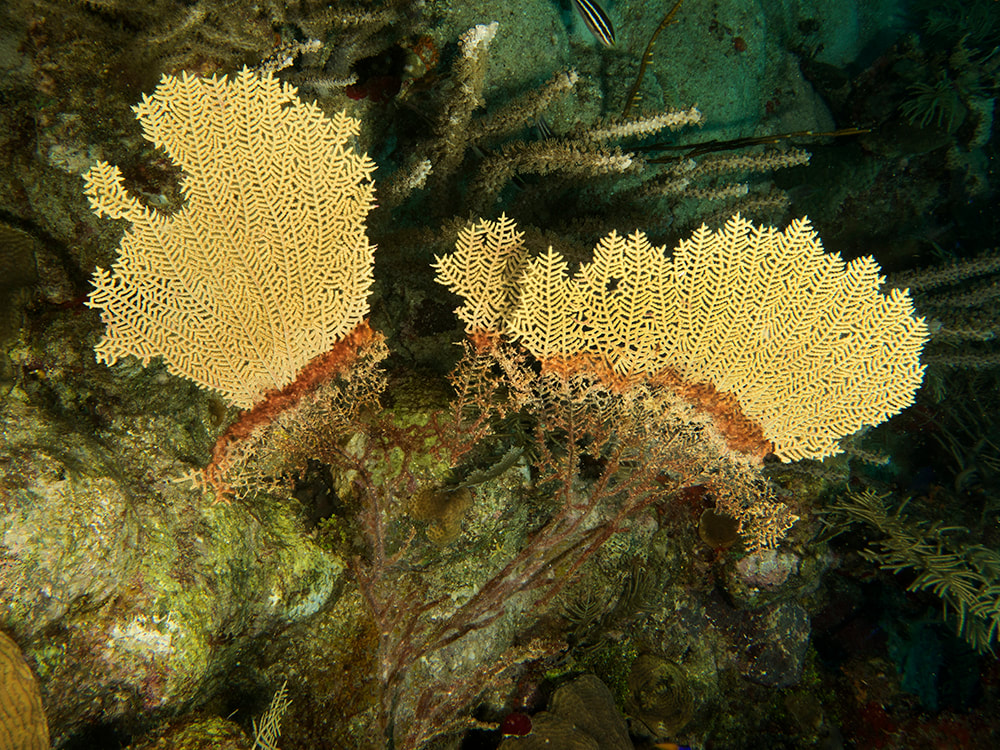

So how do we tell Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease apart from the others? First there will be the coral species that are initially affected. Typically, when the disease moves into a new area, it will first be detected on Maze Coral (Meandrina meandrites) and Elliptical Star Coral (Dichocoenia stokesi) and then it moves onto the Boulder Brain Corals (Colpophyllia natans):

These three species seem the most susceptible to this new disease. For smaller colonies they can be completely infected within just one week, showing only the white of their skeletons. This means that divers may not even get the chance to see the spread of the disease, only it's effects. From there, the disease can move on to over 20 different coral species:

Again, NOAA and the National Marine Sancuaries have made downloadable cards to identify what Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease looks like once it has infected different types of corals.

Click on any of the images below to see a full resolution, downloadable version to help with identifications: Vectors for spreading coral diseases:

Some common coral diseases are spread simply by contact with an infected coral head and can spread to neighbouring corals, even when they are of a different species, as seen in the examples below:

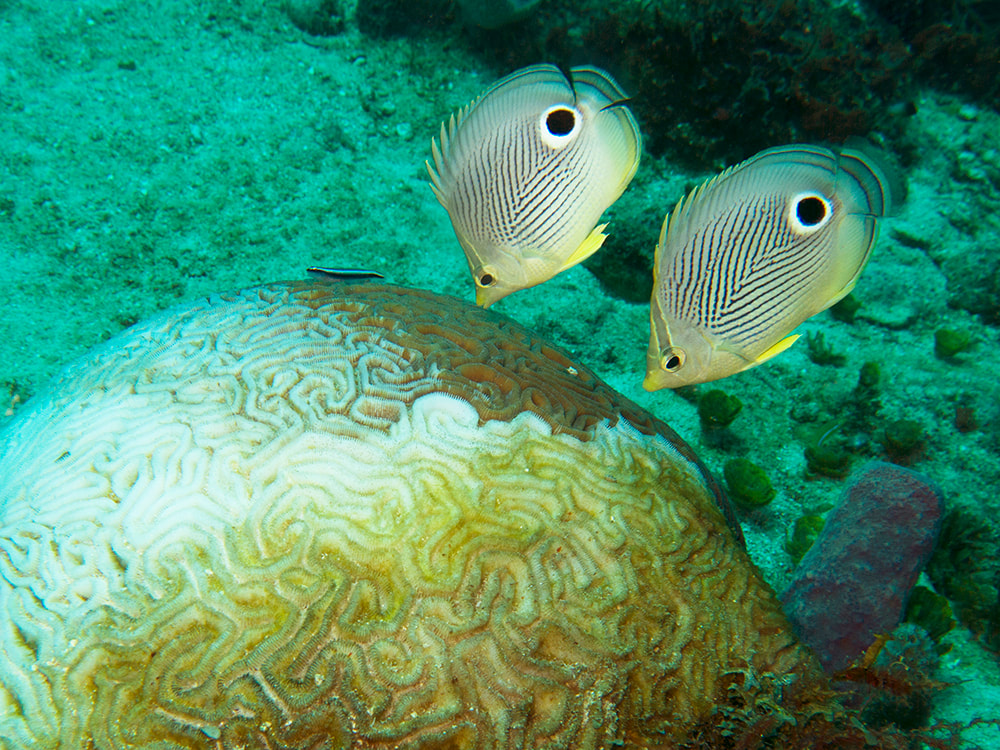

Researchers suggest that Butterflyfishes can be the carriers of some coral diseases. These are fishes that naturally feed on coral polyps and as they travel across the reef they can take the diseases with them. Fireworms can sometimes be found greedily feeding on the weakened tissue of infected corals and then may spread it onwards to other healthy corals in the area.

While little is known about Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease, one thing that most scientists agree on is that it can be water-borne. It's like the nightmare scenario from a Hollywood movie, when a rare and horrible disease suddenly mutates into something that is air-born and starts wiping out humans across the planet.

It can simply travel in the ocean's currents to find new areas to infect, or it could be released from the ballast water from cargo ships coming from the "ground zero" of the Florida region. It May be us!

There is growing concern that we divers may be the ones responsible for much of the spread of this new epidemic. If Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease is water-borne, what happens when divers move from one reef to another, or even to another part of the Caribbean?

Yes, we may be rinsing off our gear after every dive, but what about the inside of our BCD's? After any given dive, see how much seawater has accumulated in your BCD by inflating it, turning it upside down and pushing your deflate button. That's a lot of seawater that could be carrying the bacteria that causes Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease. Now imagine the diver from Florida that goes on vacation down to the Caribbean, with some of that water still in there. They get out to an otherwise healthy reef and when they deflate for their first dive, they could be releasing that mysterious bacteria right onto a new bioshere. Ironically, it may be the desire to go and visit healthy new reefs that is causing this destruction! Click here for more information on how to disinfect your dive gear before travelling to a new area. If this seems excessive, please consider what extra passengers you may be bringing with you on your dive vacations. Many dive operators in the Caribbean now have a mandatory disinfection policy for dive gear before you are even allowed to get on their boats, a practice that I support 100%! The Good News:

There really isn't much.

Perhaps the best news so far is that SCTLD does not seem to affect the critically endangered Acropora species (Staghorn and Elkhorn Corals) that have recieved so much attention lately with coral farming projects. After White Band Disease has wiped out most of these corals in the Caribbean over the last decade, they at least have been spared from the new epidemic. It's a small mercy. Marine biologist Karen Neely of Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale has had some sucess with antibiotics. Divers actually go down to the infected corals and apply disinfectants and an Amoxicillin paste, which seems to heal some lesions. Neely estimates that Florida researchers have treated nearly 1,200 coral colonies since January, 2019. With the antibiotic, “we are seeing about 85 percent success,” Neely says. But the application of this medicine doesn’t stop new lesions from appearing. “One of the big priorities is to develop colony level treatments,” she says. Until then, this paste “is the best we can hope for.” She adds: “We’ve been studying coral diseases for 30 or 40 years. We’re still in the Dark Ages. Our treatments are like sticking leeches on and hoping for the best.”

Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease has served as wake-up call to marine researchers and environmentalists. According to Dr. Andrew Bruckner, research coordinator at Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary: “Nowhere in the world have there been this many organizations coming together focused on a coral disease event. That tells you that there is intense concern about the ecological and economic impacts that Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease could have here in Florida and beyond.”

Click here for more on the work and research that is being done. It may be too little, too late for Florida's reef ecosystem; but the rest of us to the south are anxiously awaiting the arrival of this new threat and hoping that something can be done to at least slow it's progress. Meet "Einstein":

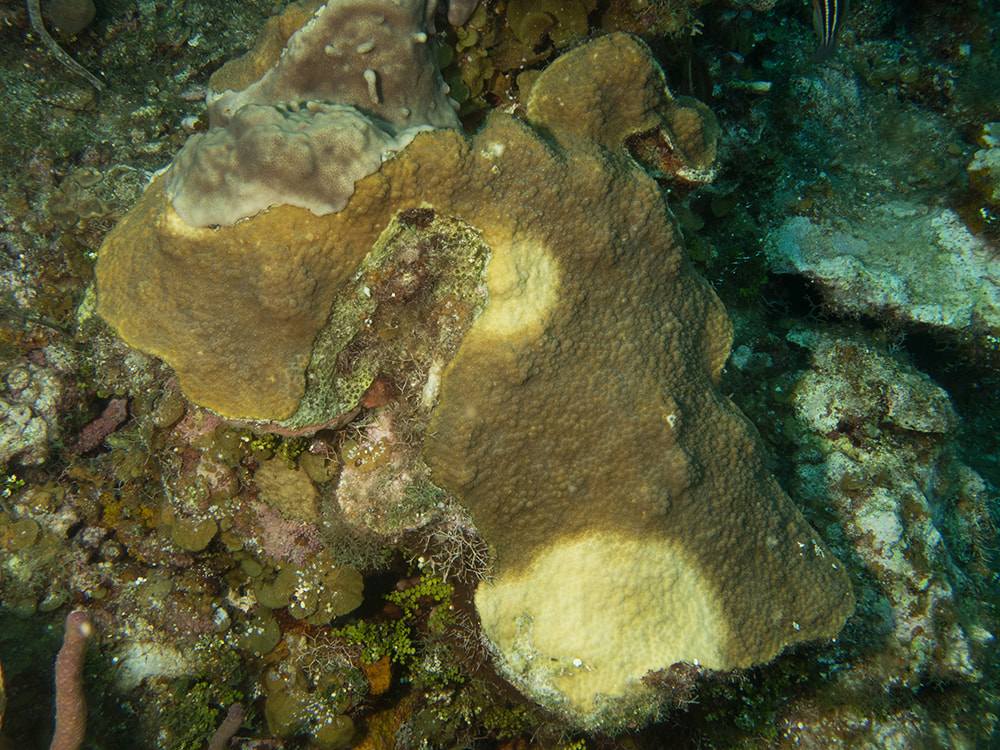

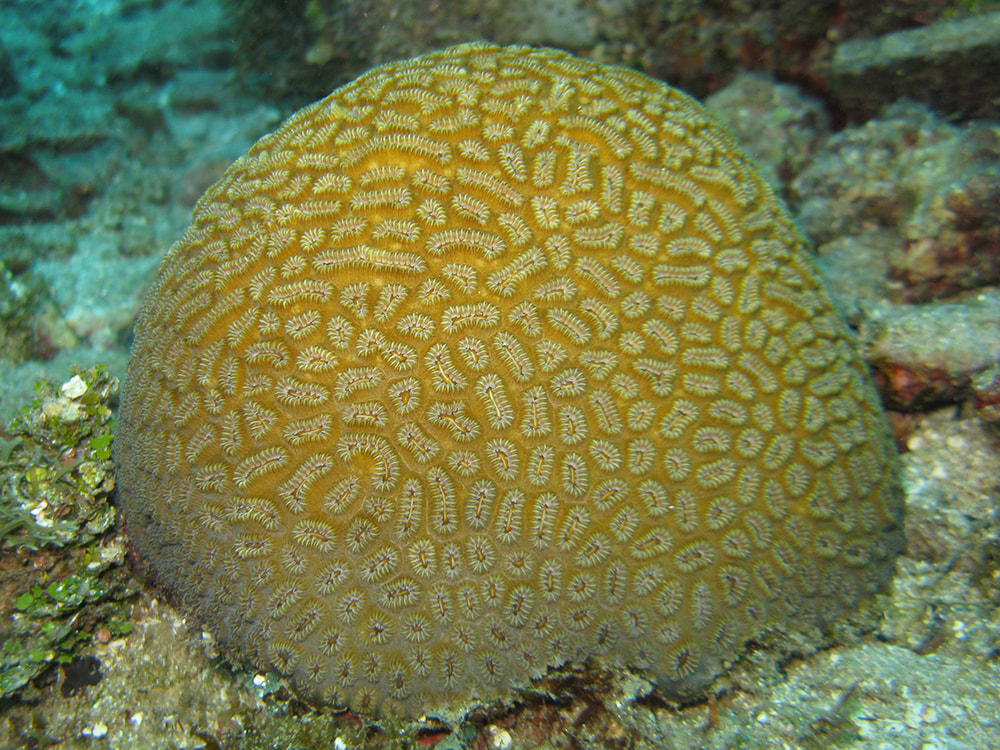

"Einstein" is the nickname I've given to this massive colony of Boulder Brain Coral (Colpophyllia natans) here on my home reef of Roatan, Honduras. (Big Brain? Einstein. Get it?)

I've known him for almost 20 years now and have shown him off to hundreds of divers over the years. Over seven feet across and almost as tall, his age can be measured in centuries!

In 2012 Einstein contracted a small spot of Black Band Disease and it quickly began to spread. The diseased tissue was removed before it could do more damage to this ancient colony, and Einstein seemed to recover. Black Band Disease is one of the few where this method can work to stop the spread of the disease.

The infected areas were soon overgrown with algae, as usually happens to dead coral skeletons, but over the next few years Einstein seemed to fight back and even began to regrow some new coral tissue over the areas that were originally infected. Einstein was slowly on the mend.

In 2015 it appeared that a small area of White Band Disease had taken root, but by the following year Einstein seemed to have beaten this one too. By 2016 the infection had stopped and normal tissue growth had stared again. A sigh of relief...

Two years ago I was horrified to see that a third disease had attacked my old friend. This time Einstein had caught a bout of Caribbean Ciliate Infection, easily identified by the band of tiny black spots and a dead white skeleton, growing outwards into the healthy tissue. Einstein was just not catching a break!

Since then, Einstein has been fighting off this disease, but it seems to be a losing battle. Caribbean Ciliate Infection is one of the slower-growing Caribbean diseases and it continues year-round. The last photo above was taken just last month.

This is how I will always remember Einstein: a large, healthy coral colony that was also host to a large family of Caribbean Neon Gobies that had set up a cleaning station. The same "regulars" would always be in the area and would come in to get cleaned, while still others would swim lazy circles around the reef, waiting their turn for the services of Einstein's resident cleaners.

You always knew you were coming up onto Einstein, even before you could see it, just from the volume of fish that were in the area to relax at the cleaning station there. These days, every time I pay him a visit, I'm wondering if I will see any sign of this terrible new disease that is rapidly spreading down from the north, and wondering how Einstein will eventually cope with it. I worry for my old friend: after centuries of survival and growth he deserves better from us. Appreciate your reefs while you have them, this problem is not going away. In fact, it's just getting started. No apologies here for the negative tone of this blog: we need to wake up and show some respect to the reefs that have given us so much in the short time we've been able to go down and actually visit them first-hand. Please share; there is far too little awareness of this impending epidemic. Mickey Charteris

4 Comments

|

AuthorMickey Charteris is an author/photographer living on Roatan. His book Caribbean Reef Life first came out in 2012 and is currrently into it's sixth printing as an expanded fourth edition. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed