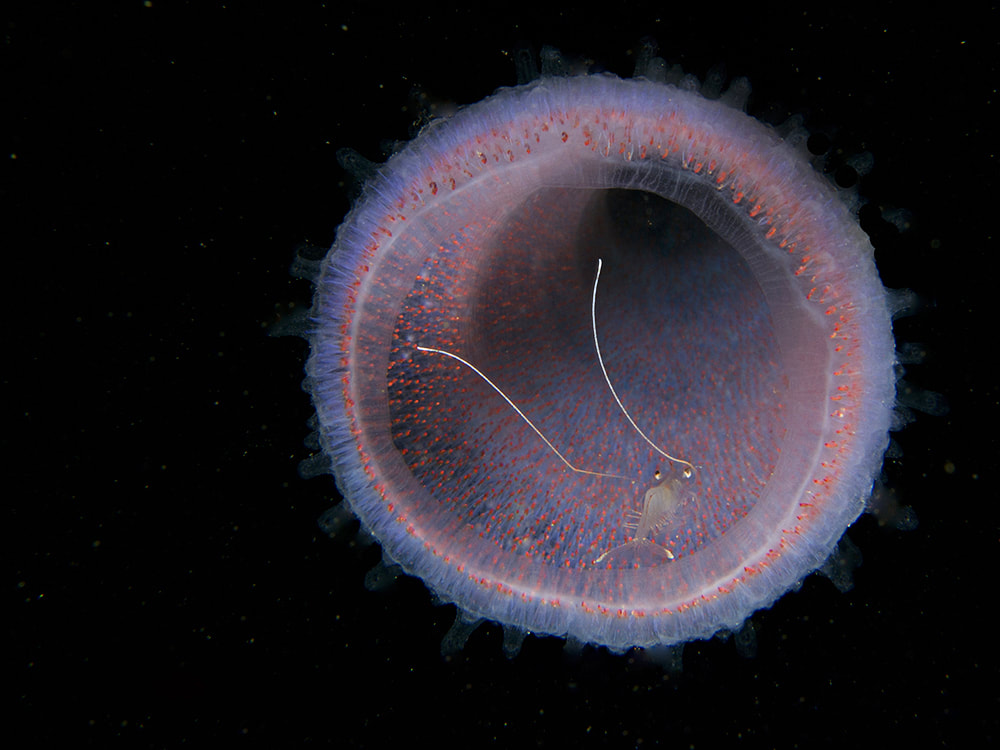

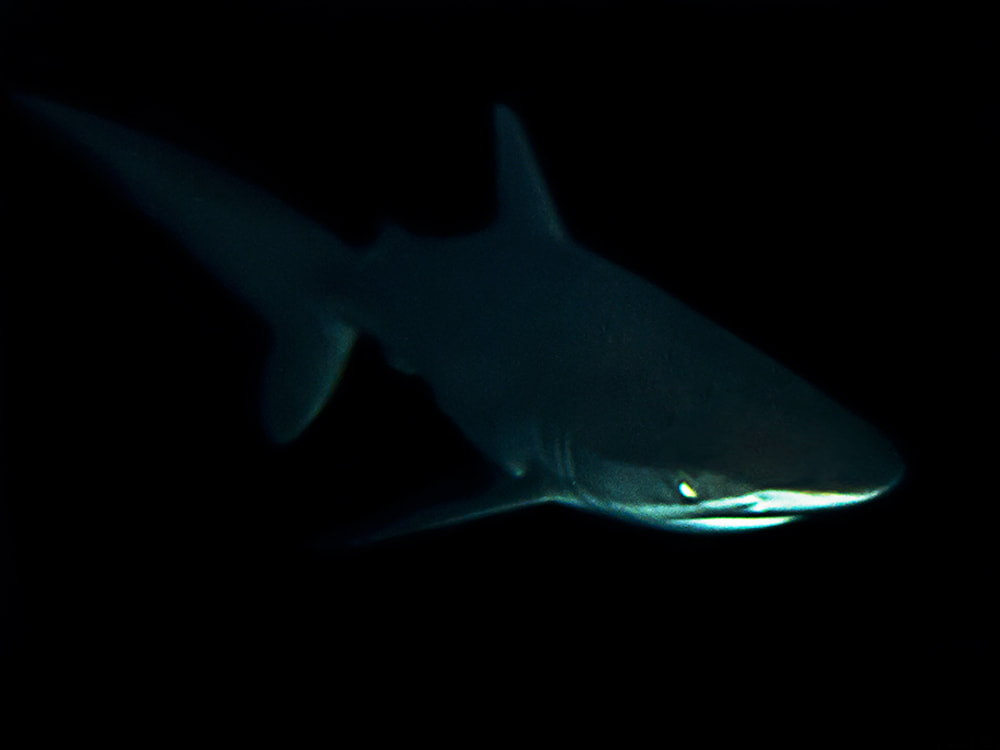

What is Blackwater diving? Many people think we are slightly touched in the head to do this thing: heading out late at night into the deepest waters we can find, throwing out a sea-anchor, lowering weighted lines into the inky water and following them down to drift in mid-ocean like bait. Here on Roatan we can do it with over 5000 feet of nothing but black water underneath us. The incredible finds out there quickly dispel any nervousness, and we are amazed at the myriad tiny creatures (and some pretty big ones too!) that we encounter. Blackwater diving is becoming more and more popular around the world, but people still ask why we do it. For some it may be the adrenalin rush, for others maybe just another feather in their diving cap or a box ticked off on their must-do list. But for me it's the opportunity to see and photograph the most bizzare and fascinating life forms I've ever seen. And shooting them is a whole new challenge for any underwater photographer. The Diel Vertical Migration: Forget wildebeests in Africa or caribou in the Arctic. In terms of sheer biomass, the largest migration on the planet happens every day in the oceans of the world, when tiny creatures make their way up to the surface to feed. They are followed and met by a host of predators. This the Diel Vertical Migration, from the Latin word for "daily." Floating near the surface of the ocean are microscopic plants, the phytoplankton. These plants are actually responsible for most of the oxygen we breath, and they are a limitless food source if they can be reached. Zooplankton like small copepods and amphipods will travel upwards from the deep ocean at night to feed here, when they are safer from predators. In the morning they will swim back down into the safety of the depths. At just a few millimeters in size, moving up through the seawater would be like humans trying to swim through a thick syrup, and they expend a great deal of energy to get to this food source. The deeper species. beyond the reach of light. actually begin to make their long way to the surface well before sunset, possibly using their own circadian rhythms to time their arrival. They risk being eaten by the host of predators that also rises up to feast in this biosphere. ( Geeks can learn more by clicking here.) Blackwater Invertebrates:

Despite their stinging tentacles, some animals have evolved to feed on siphonophores, like this larval lobster.

The fastest predators on a Blackwater dive are the squid. The most common of these here on Roatan is the Clubhook Squid, up to a foot long with very distinct sharp suckers on the ends of two hunting tentacles. They often seem dazed by our lights and even bump into us before they realize there is something bigger in the water with them. In a quick puff of ink they are gone again. Blackwater Fishes:

The larval stage of the Pearlfish has a long tail that it uses in a whip-like motion, to move quickly about or to attack its prey. It also has a very long filament on the top of its head that mimics the stinging tentacles of a siphonophore, keeping it safe as it hunts. It loses this headgear as it grows older and has the unenviable task of finding the anus of a sea cucumber to live in when it reaches it's adult stage on the reef. Other than the tiny larval versions of our common reef fish, we can also sometimes see fish species that we would never expect to find on our regular dives or even night dives, species that are only found in the open ocean such as the Oilfish and the Atlantic Flyingfish. These can be attracted to our dive lights.

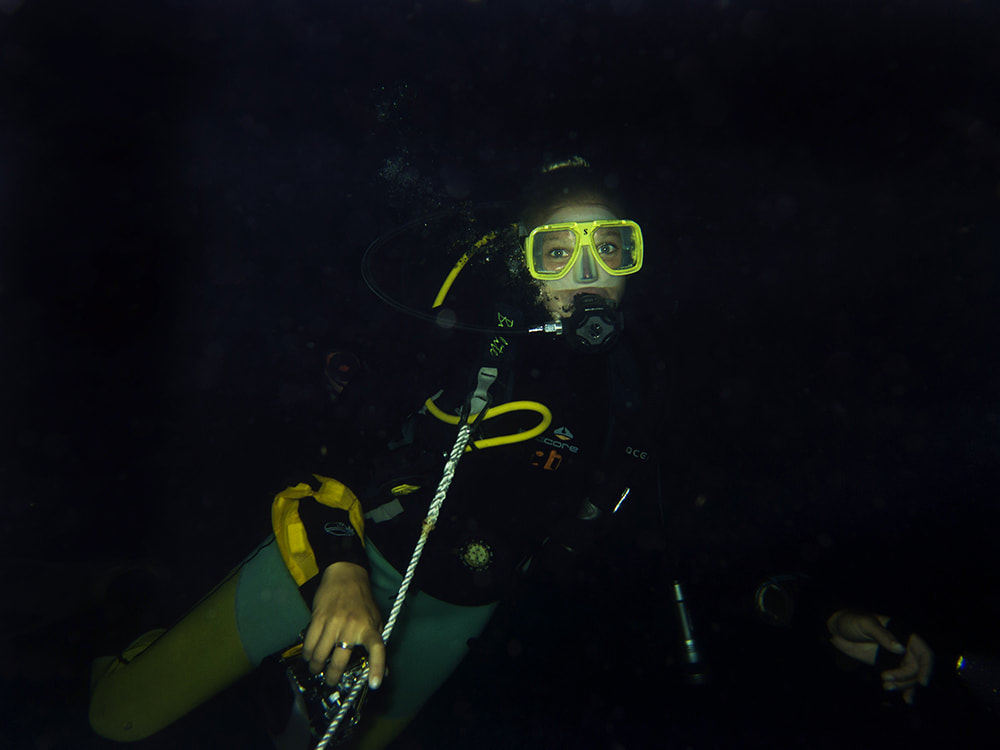

Since the team at West End Divers started pioneering Blackwater dives here on Roatan, I have been lucky enough to join in for about 20 of these fantastic experiences. My friend Courtney Blankenship (below) is the undisputed Queen of Roatan Blackwater and you can see many of her brilliant photographs here: For anyone still wondering what the attraction is, there is a very good facebook page for Blackwater photography with mind-bending images from some truly great photographers around the world. Or visit the Blackwater page of West End Divers, the shop I have been going out with here on Roatan.

For the uninitiated, it is an experience you will never forget. For the jaded diver who has "done it all and seen it all" I promise you haven't, and you will be amazed at what still can be discovered with a tank on your bank and nothing but blackness all around you! Enjoy Mickey Charteris

1 Comment

|

AuthorMickey Charteris is an author/photographer living on Roatan. His book Caribbean Reef Life first came out in 2012 and is currrently into it's sixth printing as an expanded fourth edition. Archives

August 2019

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed